- Home

- Michael O. Tunnell

Candy Bomber

Candy Bomber Read online

To Gail

—M. O. T.

Text copyright © 2010 by Michael O. Tunnell

Photographs copyright © by individual copyright holders. See photo credits on page 107 for further details. While every effort has been made to obtain permissions from the copyright holders of the works herein, there may be cases where we have been unable to contact a copyright holder. The publisher will be happy to correct any omission in future printings. All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Charlesbridge and colophon are registered trademarks of Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc.

Published by Charlesbridge

85 Main Street

Watertown, MA 02472

(617) 926-0329

www.charlesbridge.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tunnell, Michael O.

Candy bomber : the story of the Berlin Airlift’s “Chocolate Pilot” /

Michael O. Tunnell.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-60734-248-9

1. Berlin (Germany)—History—Blockade, 1948–1949—Juvenile literature.

2. Halvorsen, Gail S.—Juvenile literature. 3. United States. Air Force.

Military Airlift Command—Biography—Juvenile literature. 4. Air pilots,

Military—United States—Biography—Juvenile literature. I. Title.

DD881.T845 2010

943’.1550874—dc22 [B] 2009026648

Display type and text type set in MetroScript and Adobe Caslon

Color separations by Jade Productions

Printed and bound February 2010 by Jade Productions in ShenZhen, Guangdong, China

Production supervision by Brian G. Walker

Designed by Diane M. Earley

Half title: Candy parachutes scatter from a Douglas C-54 Skymaster.

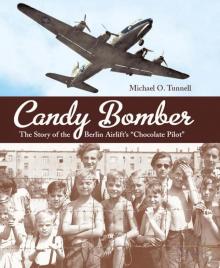

Title page: German children wait on the rubble of war, hoping to spot candy-laden parachutes drifting in the wind.

Table of Contents

Prologue

Chapter One: Bread from the Heavens

Chapter Two: “Vhat Is Viggle?”

Chapter Three: Operation Little Vittles

Chapter Four: From Little Things Come Big Things

Chapter Five: “Dear Onkl of the Heaven”

Chapter Six: Ties That Are Never Broken

Biographical Note

Historical Note

Author’s Note

Selected References

Photo Credits

Index

Lt. Gail Halvorsen, a young pilot during the Berlin Airlift (1948–49), answers letters sent to him by children from West Berlin.

Prologue

When I was a boy I would watch beautiful silver airplanes fly high in the sky, going to faraway places with strange-sounding names. I didn’t know then that when I grew up I would fly one of those silver birds myself. I never imagined I would fly food to boys and girls so they would not starve.

This book is special to me because it tells about the people of Berlin who valued freedom over food. The Russians promised them food if they agreed to live under Soviet rule, but they refused. They wanted to be free, even if that meant going hungry. Children felt this way, too. “I can live on thin rations but not without hope,” one ten-year-old boy told me. The Berlin children taught me to put principle before pleasure—to stand by what is important to you.

Lt. Halvorsen mingles with a friendly crowd at Tempelhof Central Airport.

The children I spoke to the first time did not beg for chocolate, although they had not had any for years. They were so grateful for flour they would not ask for more. Their pride and dignity moved me, and I gave the thirty children all I had: two sticks of gum. That was just the beginning. All in all, my buddies and I ended up dropping over twenty tons of candy and gum during the next fourteen months!

Those two sticks of gum changed my life forever. I received many honors and gifts on behalf of the pilots who volunteered for the candy drops. However, all the gifts and other worldly things that resulted did not bring near the happiness and fulfillment that I received from serving others—even serving the former enemy, the Germans, who had become friends.

I had so much fun on my first drop of chocolate to the Berlin children. When I flew over the airport I could see the children down below. I wiggled my wings and the little group went crazy. I can still see their arms in the air, waving at me. I was able to give them a little candy and a little hope, but they were able to fill me up with so much more.

Thank you to all those children, and to you who are about to read their story.

Gail S. Halvorsen

The Chocolate Pilot

A Douglas C-54 Skymaster flies over Berlin to land at Tempelhof Central Airport.

1

Bread from the Heavens

Nine-year-old Peter Zimmerman searched the sky for airplanes. It was 1948, and Peter stood in his uncle’s yard in West Berlin, Germany. There had been a time, three or four years earlier, when the droning of American and British bombers would have sent Peter running for cover. But World War II was over, and things had changed. Now the aircraft didn’t frighten him. In fact, he longed to see a particular American plane—one that would fly over and wiggle its wings.

In the same city seven-year-old Mercedes Simon was amazed that her wartime enemies—the Americans and the British—were now her friends. She peered out the window of her apartment, watching US Air Force planes swoop by to land at nearby Tempelhof Central Airport. The pounding of their mighty engines filled the air day and night. Like Peter, Mercedes was watching for a special plane—one she hoped would fly closer, rocking its wings back and forth.

As World War II ended in 1945, the Soviet army left Berlin in ruins. Here Russian soldiers walk amid the wreckage of buildings damaged or completely demolished by bombs and artillery shells.

West Berliners were excited to see the steady stream of great silver birds crowding their sky. Instead of bombers come to destroy, these aircraft were cargo planes that had come to save West Berliners from starvation. Each plane was filled with flour, potatoes, milk, meat, or medicine—even coal to heat homes and generate electricity for the city. Of course, there were hundreds of American and British military aviators flying into the city, but Peter and Mercedes were waiting for just one pilot. And they weren’t the only ones. Every youngster in the city had an eye on the sky, waiting to spot Lt. Gail Halvorsen’s plane.

But why was this pilot, along with the others, flying food into West Berlin? And why was it coming in on airplanes at all? It would have been much more efficient to transport the food with trucks and railway cars.

German civilians unload a sack of coal from a cargo plane. As the winter of 1948–49 approached, the precious fuel became as important as food.

The Reichstag (left), the traditional seat of German government, is visible across this open area used by West Berliners to plant gardens. Though gardens helped provide some fresh produce, they could supply only a fraction of the food needed for the blockaded city dwellers to survive.

The answers lie in what happened to Berlin when World War II ended in 1945. The Allied powers—Great Britain, the United States, France, and the Soviet Union (Russia)—defeated Germany and then divided it into four occupation zones. The Soviets took the northeastern part of the country, which included Berlin, the capital city. Although Britain, the United States, and France (the Western Allies) each occupied a zone, they still wanted a presence in Berlin—even though it was located 110 miles (177 kilometers) inside the Soviet-controlled zone. Therefore, the Allied powers agreed to divide up the city: the eastern part of Berlin would go to the Soviets, and the western part would be split into three sectors, one each for the Western Allies.

> After World War II, the Allied powers divided Germany into four zones. They also split up Germany’s capital city, Berlin. West Berlin went to France, Britain, and the United States, while East Berlin went to Russia. But Berlin lay deep in the Russian zone. When the Russians cut off land and water travel to the city, air transportation became the only way for the Western Allies to reach West Berlin.

An American cargo plane flies over Berlin as it ferries supplies into the beleaguered city. The Berlin train station, its roof blown away by bombs, can be seen to the left.

The Soviet Union had been on Germany’s side earlier in the war. When Germany unexpectedly turned against Russia, the Soviets switched their allegiance and joined Britain, the United States, and France. But Russia’s Communist government was a dictatorship, and it did not trust democracies. When the war ended, the Soviets distanced themselves from the democratic governments of their former allies. Soon Russia’s leaders made it clear that they wanted Britain, the United States, and France out of Berlin. When they didn’t leave, the Soviets cried foul by claiming that the Western Allies were forcing their democratic, capitalistic ideals on everyone in Germany.

Finally the Russians decided to drive the Westerners out by blockading Berlin—not allowing trains, cars, trucks, or river barges to reach the city. By cutting off land and water travel across the Soviet zone, the Russians intended to stop all food shipments to West Berlin. Surely after a few miserable weeks, West Berliners—who were already suffering in their war-ravaged city—would beg the Western Allies to leave so they could be fed by the Soviets. The Russians were certain Britain, the United States, and France would have no other choice but to go. As it turned out, there was another choice.

Although the treaty dividing Berlin did not guarantee travel over land and water, it did allow for several air corridors into Berlin. With this avenue of travel still open, the Western Allies decided to fly food and fuel into West Berlin in a concerted effort called the Berlin Airlift. The task was daunting. To feed over two million people seemed difficult if not impossible—certainly the Soviets thought so.

The British Royal Air Force (RAF) launched its airlift of supplies on June 26, 1948, calling it “Operation Plainfare.” The RAF flew its cargo planes into Gatow Airfield in the British sector. Besides regular aircraft, it also used flying boats named Sunderlands, which had marine fuselages resistant to their corrosive payloads of salt. They landed on lakes along the River Havel in West Berlin.

This diagram from 1948 shows the air routes pilots used to fly into West Berlin during the Air lift. As indicated by the “cross section view,” there were five different flight altitudes, which helped keep the aircraft from interfering with one another. Later, when improved navigational equipment became available, this was reduced to two flight altitudes.

Shown here in June of 1944, Lt. Gail S. Halvorsen had just graduated from flight school and received his “wings.” He flew cargo planes in South America before being transferred to Rhein-Main Air Force Base in West Germany in 1948.

The Operation Vittles statistics board at Rhein-Main kept track of the tonnage airlifted by the Americans.

The US Air Force (USAF) began its airlift on the same day as the British and dubbed it “Operation Vittles,” after the vittles, or food, it was flying into West Berlin. Douglas C-47 Skytrain and C-54 Skymaster aircraft flew into airfields in the French, British, and American sectors of West Berlin: Tegel, Gatow, and especially Tempelhof Central Airport. The cargo planes dropped out of the sky to land every few minutes, twenty-four hours a day. US pilots made as many flights as possible before fatigue required new flight crews to take over. One of these pilots was Gail Halvorsen, a young lieutenant who had just arrived in Germany.

In July 1948 Lt. Halvorsen arranged for a jeep tour of war-torn Berlin, during which he snapped this photograph of the Reichstag. But before he left Tempelhof to see the city, he had a fateful encounter with a group of German children—a brief visit that would change his life forever.

2

“Vhat Is Viggle?”

Lt. Halvorsen wanted to see more of Berlin than Tempelhof’s airfield, such as the bunker where Adolf Hitler had spent his last days. But the USAF cargo planes were allowed so little time on the ground that a sightseeing trip was impossible. The only option was to skip some sleep and hitch a ride on another C-54 when he was off duty. One warm day in July, Halvorsen decided to do just that. He arranged for a jeep and a driver to meet him at Tempelhof and take him into the bombed-out city.

Before the jeep arrived Lt. Halvorsen walked to the spot where the planes approached for their landings. He wanted to aim his 8 mm movie camera at the war-battered apartment buildings that rose up at the end of the runway. The C-54s skimmed across the rooftops, their four propellers slicing the air as they plunged downward for a bone-jarring landing on the runway of pierced-steel planking. It was a sight worth catching on film.

A C-54 comes in over apartment buildings to land at Tempelhof. The runway was covered with temporary pierced-steel planking (visible in foreground) that made for a noisy, bone-jarring landing. The planking was later replaced with pavement.

As Lt. Halvorsen neared the wire fence at the end of the landing strip, he noticed a ragtag group of about thirty German children, between the ages of eight and fourteen, gathered on the other side. By the time he had filmed the first plane roaring over the chimneys, “half of the kids were right up against the fence across from me,” Halvorsen remembers.

He turned, smiling at the children. “Guten Tag. Wie geht’s?” (“Hello. How are you?”), he greeted them, using most of the German he knew. The youngsters not already standing at the fence rushed forward to peer through the wire, and the young pilot was inundated by a torrent of greetings in both English and German. Two or three kids emerged from the smiling, giggling group and in broken English began to ask questions for the rest.

“How many sacks of flour are on each aircraft?” one of them inquired. Lt. Halvorsen stepped closer to the fence and told them that a C-54 could carry two hundred sacks weighing a total of twenty thousand pounds (nine thousand kilograms). But as the kids peppered him with questions, the lieutenant began to understand that these young West Berliners cared about more than food.

A typical group of German kids peer through a wire fence at the end of the runway at Tempelhof.

German civilians unload sacks of flour. Each sack weighs 100 pounds (about 45 kilograms).

“We have aunts, uncles, and cousins who live in East Berlin,” said one of the boys, “and they tell us how things are going for them.” As the Soviets tightened their control on East Germany, they confiscated property, suppressed free speech, canceled the free elections proposed by the Western Allies, and denied a host of other civil liberties. They even went so far as to force thousands of skilled German workers to relocate to the Soviet Union.

A girl with “wistful blue eyes,” wearing trousers “that looked like they belonged to an older brother,” also spoke up. “Almost every one of us here experienced the final battle for Berlin,” Halvorsen remembers her saying. “After your bombers had killed some of our parents, brothers, and sisters, we thought nothing could be worse. But that was before the final battle…. [Then] we saw firsthand the Communist system [of the Soviets].”

Here is yet another scene showing the destruction of Berlin by the Russian Army.

Lt. Halvorsen visits with German children standing behind a fence at the end of the Tempelhof runway.

Lt. Halvorsen knew these children were lucky to be alive. Frequent American bombing raids and then the final assault by Soviet troops had taken a devastating toll of lives. He knew that during the last years of the war, these same kids had scratched for what little food was available. So he was surprised to hear them say that they could get by with very little for quite a long time, as long as they could trust the Western Allies to stick by West Berlin. Though they worried about going hungry, the children seemed to agree that they were just as concerned abou

t losing their newfound freedoms. “These young kids [gave] me the most meaningful lesson in freedom I ever had,” Halvorsen recalls.

The lieutenant’s eyes panned the thirty hungry faces, and his heart skipped a beat. These were the children he was here to save—children who’d grown up knowing little else but war. “I’ve got to go, kids,” he said reluctantly. He knew the jeep was waiting to take him through the rubble-strewn streets of Berlin for more photos.

Fifty yards away from the fence, Lt. Halvorsen stopped. He couldn’t get those youngsters out of his head. He knew because of the war they hadn’t tasted candy in years. In other parts of the war-torn world, kids begged American servicemen for sweets, yet not one of these kids had asked him for something. He reached into his pocket and felt two sticks of Doublemint chewing gum. Turning back to the fence, he broke the sticks in half, wondering if it was a mistake to give the four puny pieces to thirty sugar-starved boys and girls.

Expecting the children to squabble over the gum, the lieutenant watched what happened in amazement: there was no fighting. The lucky four who had plucked the half sticks from his fingers kept the gum, but they ripped the wrappers into strips, passing them around so everyone could breathe in the sweet, minty smell. “In all my experience, including Christmases past,” he recalls, “I had never witnessed such an expression of surprise, joy, and sheer pleasure.”

Just then another C-54 roared overhead and landed, tires screeching on the runway. “The plane gave me a sudden flash of inspiration,” Halvorsen remembers. “Why not drop some gum, even chocolate, to these kids out of our airplane the next daylight trip to Berlin?” Of course, the lieutenant knew he might never get permission from his commanding officer for such a stunt, but why not do it anyway? Just once. Surprising himself, Halvorsen hurried back to the fence and announced his plan to the eager children. He told them that if they would agree to share equally, he’d drop candy and chewing gum for everyone from his plane the next day.

Candy Bomber

Candy Bomber